Fire Walk With Me

On living with fire in Los Angeles.

The essay everybody posts when big fires break out in Los Angeles is thirty years old this year. “The Case for Letting Malibu Burn,” written by Mike Davis in 1995, noted that Malibu was the wildfire capital of North America and possibly the world. I’m guessing that’s still true. It was probably true in 1962, too, when the Los Angeles Fire Department produced this short documentary about a fire that ravaged Bel Air and Brentwood the year before. (If you lost your home this month, you may not want to watch the film right now.)

But look at Mike’s lead sentence: “Late August to early October is the infernal season in Los Angeles.” This is January. Flames have engulfed the city in wet season.

Anyone who grew up in Southern California grew up knowing one thing Mike Davis did: The Santa Monica Mountains are prone to fire because chaparral is designed to burn, but only every thirty years or so. And fire season is supposed to be just that—a season.

But fires are starting to behave differently in the Santa Monica Mountains, as they are all over California and the West.

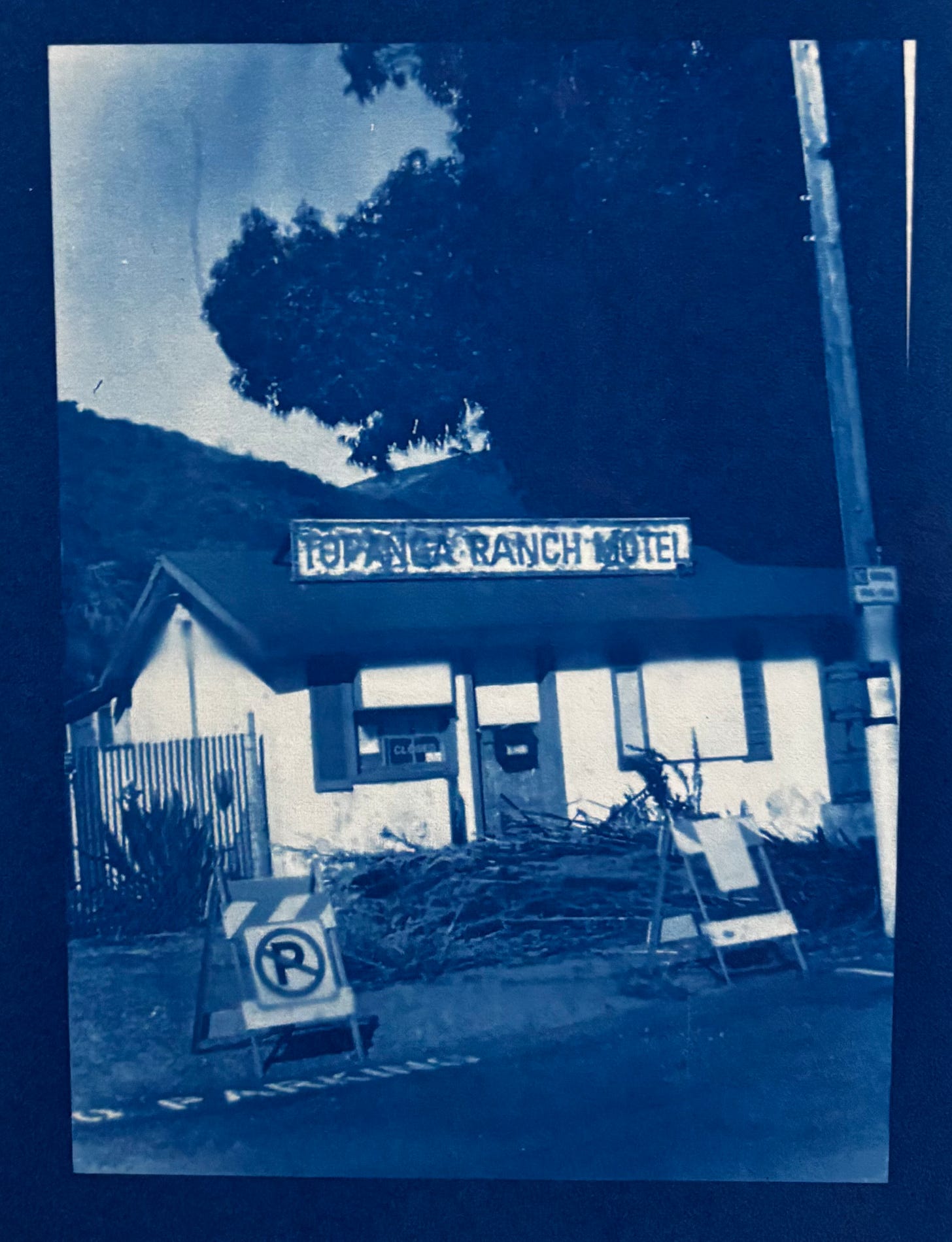

I lived in Topanga Canyon from 2017 to 2022. During much of that time, I was working as an op-ed editor at the Los Angeles Times. One of my main beats as an assigning editor was climate change, and the city’s readiness and lack of readiness for the inevitable. I have no idea how many pieces I edited about warming overall—it must be close to a hundred—but a good portion of them were about fire and water in California.

Topanga has had a few galvanizing fires. The big one in recent memory happened in 1993. It’s known as the Old Topanga fire because it ransacked Old Topanga Canyon. It was small by today’s megafire standards—18,000 acres burned, some 350 homes destroyed—but unique conditions created an “enormous vacuum” in the sky and 200-foot flames in places. After this fire, the town formed the Topanga Coalition for Emergency Preparedness, a volunteer-run organization known as TCEP (pronounced TEE-sep). Soon after my husband and I moved to the canyon, the group sent us a binder of emergency instructions, organized by calamity—fires, earthquakes, mudslides. That might sound alarming but the reality is that L.A. is a pick-your-calamity city. Topanga may be in a high-risk fire zone, but it’s not a bad place to be in an earthquake.

I didn’t appreciate the importance of all this preparedness until the Woolsey fire, which tore through the Santa Monicas in 2018, a year after we moved to the canyon. We learned about the fire at night, when a text landed from PulsePoint, the app that connected the Los Angeles Fire Department dispatch system to our phones. It was burning in Agoura Hills, about fifteen miles west of the house we were renting. It wasn’t contained at all but it was only 2,000 acres in size. We went to bed. Maybe six hours later, our power went out. When we left for work that morning, we didn’t know we were evacuating.

I don’t remember how many days we were gone. We started out at our friends’ house in Venice and moved to an Airbnb and then to another Airbnb. I do remember wandering Abbot-Kinney in a daze, wearing my work shoes, Spuds MacKenzie pajamas lent to me by a friend, and an N95 face mask, because it was raining ash. As so much of L.A. learned this month, the lack of solid, real-time, useful information can cause a lot of chaos and added stress in a fire. At one point during the Woolsey, Mayor Garcetti’s Twitter account posted that the fire “continues to burn” in Topanga, and our hearts sank. Unnecessarily, it turned out. Topanga wasn’t burning. Over and over that week—was it a week?—TCEP was our only reliable lifeline. (Wrote about that here.)

Later I went to see the burned areas up close, and if and when it’s possible, I suggest you take the time to do the same. During the Woolsey, wide swaths of the mountains were torched. Fences that weren’t made of wood wilted and melted to the ground like cooked spaghetti. But in places where the fire moved more slowly, you could glean things.

There was a striking amount of variability in Point Dume. On a single street, one house would be standing, the next gone, the next standing, the next gone. People who’d stayed behind to protect their homes were swapping war stories. One guy had spent the previous night wrestling a stubborn bougainvillea plant off of his house. Another told me wearily, “eucalyptus are the enemy.” (Apparently eucalyptus trees can get hollowed out from the inside and then crash onto your house, where, because their oil is combustible in high heat, they behave like dynamite.) A lot of it came down to plants. Another guy lost his childhood home but not his father’s music studio on the same property, most likely because of the location of his mother’s garden, he’d concluded. Every single person was surprised that the fire crossed Pacific Coast Highway. “Fires don’t jump PCH,” was the refrain I kept hearing. The Woolsey jumped PCH.

It’s one thing to see the burn zone at ground level, quite another to see it from above. A month after the fire, I got word that the guy behind 69 Bravo wanted to give local journalists helicopter tours of the Woolsey path. 69 Bravo is a thirty-four-acre site overlooking the Pacific that a former radio executive who goes by Simon T converted into a helipad and water base for L.A.F.D. helicopters. The base has been there since 2010 but few of the coastal residents whose homes are saved by it regularly know it exists. I could get a tour on one condition, I was told—that I not try to do a story about Simon T. (Matt Stiles of the L.A. Times eventually got him to agree to an interview. You can read the story here.)

We lifted off from the bluffs and flew up the coast a bit, over burned homes along PCH, then cut inland. As we made our way over the mountains, many of the ridges looked like moonscapes. The Woolsey started near the Santa Susana Field Laboratory, a onetime rocket and nuclear testing facility above Simi Valley. We circled over the site and then followed the fire’s main path back to the beach. Simon T narrated with time stamps—it started at 2 p.m. in the afternoon, jumped the 101 within fifteen minutes. He wanted me to understand how quickly Topanga could get overtaken if the Santa Anas were blowing in a certain way. Later, another person at 69 Bravo put it in stark terms: Topanga could be “the next Paradise,” meaning Paradise, California, the town in Butte County that was leveled in the Camp fire a month earlier.

You’d think all this would have dissuaded us from buying a house in Topanga. But one takeaway from the Woolsey seemed to be that all bets were off, that anywhere could burn. At least Topanga was prepared.

The Woolsey changed the way we looked at homes for sale in the canyon. We declined to make an offer on one house we liked because it was on a one-lane street in a dense neighborhood. The house we ultimately bought had a lot of landscaping done with cinderblocks and an arroyo wall lined with concrete, features that may have seemed a little rough to us before but which now looked beautiful.

During the three years we lived there, we did a lot of “hardening.” We cleared brush. We covered vents. We created “defensible space.” We removed the old cedar shingles and replaced them with fiber cement. (I am bullish on Hardie board.) At one point I considered writing up a description of everything we did, but after you’ve done the basics, hardening is site-specific. (I did assign this piece during a stint in the paper’s features section.) We also bought walkie-talkies and tuned in for “Top of the Hour” test broadcasts and neighborhood roll calls on TCEP’s radio network. (Wrote about that here.)

I don’t know for a fact that the red-flag warnings and evacuations got more frequent, but it felt like they did. For sure the P.S.P.S. got more common. That stands for public-safety power shutoffs. Southern California Edison would turn off the power in our area during strong winds to prevent their equipment from igniting fires. This was a good thing. But because there were no cell towers near us and we were dependent on Wi-Fi to use our phones, the outages also meant we had no means of communication. More and more, we’d just leave the canyon.

I want to be careful how I say this part. I don’t know what made me think it, but I remember exactly where I was when it sunk in. So much of our vigilance was focused on accidental fires. What about intentional ones? The next week or the following, someone deliberately lit a brush fire in the Palisades, near the Trailer Canyon trailhead. It burned a good portion of Topanga State Park.

Had we not sold our house a year later, we would have kept hardening. I’d found news stories and blog posts from up and down California about houses that were left standing after intense fires, and a significant number credited aloe plants. I was planning to go wild at a nursery near Santa Barbara called Aloes in Wonderland. Fire wasn’t the only reason we left the canyon but it was one of them. Everyone has a different tolerance for risk. Ours was depleted over time.

In the five years that we lived in Topanga, we dealt with many different fire scenarios. This month brought a new and unimaginably nightmarish one—for all of L.A., obviously, but also for us. When the fires exploded we were in Woodland Hills, in a grid-like neighborhood along the 101. Although we weren’t terribly far from the Palisades fire burning on the other side of the mountains, or from the Sylmar fire burning in the Valley, we were under blue sky.

Then, Thursday afternoon, a new fire broke out in West Hills, so close we could see it, allegedly started by a man with a blow torch. It grew to 1,000 acres in a matter of hours. Instantly we were back in that familiar state, hastily gathering our documents, the dog kibble, the toiletries, the rumpled clothes on the floor. The traffic lights were already out by the time we reached Ventura Boulevard. We got on the 101 and started heading east—to where, we didn’t know. From the freeway we could see the plumes of all the major fires at once, above Sylmar, Altadena, the Hollywood Hills, the Palisades, and now, in our rearview mirrors, West Hills. Once again, and much more catastrophically for the city, the lesson is that all bets are off, that anywhere can burn.

Work in news long enough and you get to know the routine real well. We start with the immediate questions. Why did the hydrants lose pressure? Why was the Palisades reservoir empty? Why didn’t the fire department put trucks in the Palisades and Altadena ahead of time? Why do we have only two Super Scoopers? And what water, exactly, are all those private firefighting crews using?

For a while there will be a bigger appetite for fire and climate op-eds. Someone will point out, again, that fires are getting bigger. Someone else will say, again, that certain fires can’t be fought. Others will make the case that our water supply remains precarious, and that our centralized power grid leaves us vulnerable. We’ll have more pieces than usual about the need for different building materials and more responsible planning practices. For whatever reason the op-ed I’ve thought about most in recent days is this one, about Alaskans adapting to their changing forests. Although warming is global, the writer argued, adaptation will have to be local.

I live most of the time in Taos, New Mexico, now. Fire will come through there too, no doubt, probably sooner than later. I won’t have TCEP to rely on, but the terrain where I am is flat and wide open. I like to think I’ll see it coming. On the whole I feel less anxious. One hot day last summer, though, I came home from the post office and saw one of my neighbors burning a mound of trash in the wind. I started to twitch.

Beautifully written, Abby! A powerful piece on resilience and preparedness.

Great information and thanks for all the insights and community services you shared on your IG . Great work!